|

|

|

| Home | Essays |

Wikipedia | Resources | Portals & Archives |

|

Maya |

|

||||||||||||

"It is not enough to have a superficial understanding of Maya; it is necessary that Maya should be understood as it is, i.e., in its reality." "Maya is the falsity of the process of thinking." "If the true is known as true or if the false is known as false, there is no falsehood, only a form of knowledge; falsehood consists in taking the true as false or the false as true, i.e. in considering something to be other than what it is." "What makes It (Infinite Intelligence) think falsely? What makes It bound by Maya? Sanskaras!" |

Defining Maya Elucidation on the topic of Maya based on a study of the teachings of Meher Baba by Christopher Ott and Stelios Karavias |

|||||||||||||

|

It is very hard to give a simple explanation of Maya, the originally Hindu concept that Meher Baba emphasized in his books. Yet from the point of view of a person trying to get established in the path of gnosis no other concept is more important to grasp clearly. Having a definition of a word is not the same as having a real intuition of what it means, one that is true to its original sense and also useful to the mind. Mere definitions also generally omit the ontology (issues of being) of the entity itself, something Baba addresses as being important to understand in regard to Maya. And definitions don't describe the various misconceptions that can potentially grow up around a word. Here therefore, a slightly different approach is taken toward giving a clear, immediate, and psychologically useful intuition of what Maya is, that approaches the question of Maya in parts. 1. Etymology of the word Maya The concept of Maya is often attributed to Adi Shankara (or Sankara), the Indian philosopher who perfected the philosophy known as advaita vedanta in the 9th century, a philosophical position of absolute unity that Meher Baba upheld. However, according to Robert C. Gordon, the first use of the concept of maya in a way that proved helpful to all Vedantic development must be credited to Gaudapada, the teacher of Govinda, Sankara's own philosophical master. Gordon remarks: "That the mayavada of Vedanta can be traced to Buddhist origins should come as no surprise... Pivotal to Sankara was Gaudapada's assertion that maya was the source of the world, and maya was the key concept that enabled Sankara to bring order and coherence to the mass of Vedic scripture." [Emerson and Sankara, Robert C. Gordon, Ph.D.] The word itself comes from the Sanskrit roots ma ("not") and ya, generally translated as an indicative article meaning "that". The term is frequently said to mean "illusion" or "appearance" in Sanskrit, but this is very misleading. We will explain why in parts 3 and 4 below. Other literal interpretations of its meaning include "deception" [Encyclopedia of Eastern Philosophy and Religion] and "false attachment". [GS Glossary] The Glossary of God Speaks defines Maya as "That which makes the Nothing appear as everything. The root of Ignorance. Shadow of God". But this is hardly edifying by itself without elaboration. We are left wanting to know what "that" refers to, and equally what it doesn't. Left to our own western devices we might assume "that" refers to the devil, although it doesn't. Also, in what sense is Maya the shadow of God? Does Meher Baba actually say this anywhere? But before looking into all of these matters, we should have at least some concept of what Maya is. In order to have some idea of what we are talking about, suffice it to say for now that Maya simply means the principle of illusion that acts upon the mind, and we'll clarify later. 2. An example of Maya at work Maya, whatever it be ontologically, is an influence upon one's mind. Baba clarifies that it is not the illusions that we see, such as the physical world around us or the subtle or mental worlds that advanced wayfarers may perceive. Rather it is the power of the mind to make misidentifications and reach wrong conclusions. Where a simple definition can be a bit abstract, an analogy is often helpful. Shankara originally gave the following analogy to explain the workings of Maya. Suppose you are walking along a path at dusk with no flashlight. Dusk is the hardest time to see clearly, as the eye is most adapted to seeing either at night or in the day. Just before the light is largely extinguished and our night seeing comes into full effect, there is a magic moment when it is as if the shadows come to life. At that moment it can be hard to make things out. Now suppose while walking in the dusk light we come upon a stick in our path, just far enough ahead that we can't quite make out what it is. We might easily mistake this stick for a snake and be frightened. But if we gather our courage, a closer inspection reveals that the snake was really nothing but a stick. And our heart lightens. How many people have not had a similar experience while walking in the evening shadows? According to Adi Shankara, that is what Maya is like. Being semi-awake, in twilight as it were, we take the eternal, indivisible, and omnipresent Reality to be this false, limited, suffering, temporal duality, formed from our impressions; we take the false to be real, the real to be false. We are deluded by Maya. 3. The various misconceptions about what Maya means There are several ways that Maya can be misunderstood. Some are extremely common in the reading material available in libraries and appear in some form in nearly all published definitions. Others are merely potential, but equally important to address, especially for westerners who are often tempted to read into Eastern concepts their own brand of externalized thinking. Here we'll name and address these misconceptions. The most common misconception about Maya is simply that the word refers to the illusion, i.e. duality, the Universe, the things seen. This misunderstanding is partially understandable since sources so often repeat that the word Maya comes from a Sanskrit word literally meaning "illusion", which is actually only a favorite among several "literal" interpretations of its root. Regardless of the word's etymology, Meher Baba says that Maya is the creator of illusion and not the illusion itself. Another equally common misconception that Baba addresses, is that Maya is itself an illusion, like the illusions that it produces, and therefore its activity is untrue, not a fact, or not a real spiritual principle. One result of this misunderstanding is the false belief that Maya, by some trick of its own doing, is beyond human understanding. Meher Baba addresses these misconceptions about Maya rather bluntly.

The last misconception mentioned, that the human mind is incapable of grasping Maya due to the effect of Maya, is especially unproductive. If the mind could not grasp the fact of Maya's influence and its consequences, then how could the mind progress in its attempt to discriminate between the false and the real, the impermanent and the permanent, in its quest for the Absolute Truth? How could human beings begin to tread the path of dnyana? It is necessary to understand Maya in order to defeat its effect within one's own thinking. The idea that Maya is beyond mortal comprehension is a way to opt out of the path of gnosis, but not a properly applied dimension of gnosis itself. Meher Baba not only encourages the aspirant to try to grasp what Maya is, but urges him to go beyond a mere superficial understanding of it and take note of its operation in his own experience.

The next misunderstanding is less common, but because it could conceivably occur, it is equally important to address it, if only to prevent it. That is that Maya is somehow analogous to the Christian and Islamic concept of the devil. This externalization of Maya is, of course, potentially disastrous. The next misunderstanding is less common, but because it could conceivably occur, it is equally important to address it, if only to prevent it. That is that Maya is somehow analogous to the Christian and Islamic concept of the devil. This externalization of Maya is, of course, potentially disastrous.

Maya plays in the human mind and in the imagination of Ishvara (the unaware but formative aspect of God according to Hindu philosophy and Meher Baba). But it does not linger beyond them and it is not a trickster, tempter, or externalized force in any way imaginable. In fact, the notion of Maya going about tricking people could itself be viewed as a first rate example of Maya acting upon the human imagination, a kind of self-deception in itself. In that, such a notion would serve to illustrate the process of Maya and its many wonders when unrecognized in one's own mental workings. Beyond that, and inspite of popular simplifications, the whole subject of an external Maya is best forgotten. 4. Encyclopedic and dictionary definitions of Maya Here we give some encyclopedic and dictionary definitions of the principle of Maya. While these published and online definitions of Maya are helpful in getting some understanding of what Maya can refer to in modern parlance, and since no stone ought to be left unturned for grasping what Maya is, here we will go to some length to point out any misunderstandings that could be taken from these definitions where they occur. The first is from "The Encyclopedia of Eastern Philosophy and Religion," produced by Shambhala Publications.

This definition is quite good, has depth, and is concise and clear. Translated from German, the publisher gives no indication of its authorship. Its one error (if it could be called that) might be that it refers to Maya as "appearance" and "cosmic illusion", which could again give the impression that Maya is the illusion itself. As already explained, it is truer to say that Maya is the self-deception that causes the appearance of illusion or the taking of the illusion to be real. Wikipedia, the free Encyclopedia that anyone can edit, is always changing and no one statement about its content will hold good forever. Articles may grow worse or better, but in our experience, it usually improves over time more than it degrades. While its article titled "Maya" is useful and ought to be taken advantage of for its many valuable details and external references, here we'll point out some sections from it that might be misleading due to its choice of terms. The lead sentence of the article is excellent.

Incidentally, two of those mystics that the editor does not name, who hold that Maya is real, would include Adi Shankara, the original philosopher who conceived of Maya, and Meher Baba. However, it might be even clearer to say "is not an illusion" since to say Maya "is real" might by some be misconstrued to mean real in some tangible or ethereal sense. Still, it's a nice lead. But in the section beneath titled "Maya in Hindu Philosophy" it continues:

While, to be fair, this may in fact be how Vedanta is presently taught somewhere in India, it still constitutes yet another example of that most common of all errors that Meher Baba chose to emphasize and clarify, as mentioned in the preceding section on misconceptions. Another section on Maya in Wikipedia is developed directly from Meher Baba's Discourses. It appears in the Wikipedia article "Discourses (Meher Baba)" under the subheading "Maya".

The following sample of five definitions are from online dictionaries and websites that attempt to explain or define Maya. By now the common misconceptions should be obvious and we will not be pointing them out.

5. What Meher Baba says about Maya Here at last we will get into some of the meat and potatoes (or chutni and dal) of this examination of Maya. Meher Baba makes numerous statements on the subject of Maya. On top of committing 22 pages of Discourses to explaining Maya and its effects, Maya appears numerous times in the Supplement to God Speaks, in several parts of The Nothing And The Everything, and copiously in Infinite Intelligence (see especially Series III and Series VIII). On the subject of Meher Baba's treatment of the subject of Maya, one point is especially worth noting. In terms of shear number of instances, Meher Baba most often refers to Maya as "the principle of illusion" or "principle of ignorance" [Di Volume III Pages 137, 146, 155, 161]. Thus the word "principle" seems important. To understand how Baba is using the word "principle" to categorize Maya, it is good to see what meanings the word has in English, for there are various.

It seems reasonable that Baba could be using the word "principle" in its sense as primary source, or origin. In such a sense we say that the principle of an effect is the cause that produces it. Another use of the word "principle" in English is as a fundamental law, and God Speaks does in fact refer to human ignorance as "governed" (inferring a law) by the principle of Maya [GS pdf version p. 269]. In the very same sentence in God Speaks, Maya is also referred to as a "force". There is in fact no linguistic contradiction in using these two terms together. Compare, for instance, how science speaks of the law of gravity. Gravity is a principle, both in the sense of gravity being a primary cause of an effect and as a governing law. In fact we refer to gravity as the force that acts upon those governed bodies.

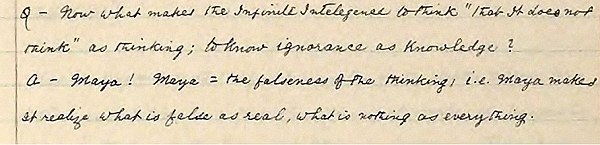

Hence, perhaps one way to look at Maya, while getting a sense of what it is and how it operates, is to look at it as somehow analogous to gravity (of course not in the physical sense). Just as the natural law of gravity serves as the principle to bind and form the physical components of the finite corporeal Universe, the Divine Law of Maya binds and forms the Illusion and its laws out of infinite Divine Imagination. Here are some selected statements about Maya that seem especially pertinent and helpful. We begin with a quote from the Infinite Intelligence notebooks. Due to a degree of concern some people have expressed over the closeness of the published edition to the flavor of the original, both forms are given here:

The following are from God Speaks. The first is from the Supplement by Indian Sufi scholar Dr. Ghani Munsiff and the second is from the Glossary written by American Sufi Lud Dimpfl.

Finally a quote from the Discourses by Meher Baba, developed by professor of Indian philosophy Dr. C. D. Deshmukh from notes given him by Meher Baba.

6. How Maya relates to sanskaras To understand its functioning, it is also valuable to see how Maya is connected to the sanskaras. Let us recall what sanskaras are. They are the imprints or impressions left on the mind by previous experience.

Once impressed on the mind, sanskaras then color all our future perceptions, prompt our judgments of those experiences, and thereby condition new experiences. Sanskaras are in a sense no more than the operation of Maya on a psychological level within the individual. Thus, a good way to think of sanskaras is as the simplest psychogenic working part of Maya - which is the power to make false judgments. Sanskaras are thus the mechanics by which Maya operates within the human mind and by which it gains its formative power. For it is our sanskaras most fundamentally that produce our phenomenal world. Maya then is the broader cosmic priciple of forming illusions and of taking the false to be real and the real to be false, the fundamental principle underlying all self-deception and illusioning. And the sanskara (the single instance of an illusory impression) is that event put into practice. Thus, while the sanskara is the working part of our formative psychology out of which we create false distinctions (and thus the world), it is Maya (the ability to self-deceive) that makes the sanskara and its resultant false judgments seem real and the real false. 7. Conclusion; synthesizing what has been said So how do we now integrate all these sections into a coherent and spiritually useful understanding of Maya? To begin with, grasp that Maya is not a thing. It has no substance. It is a mode of conceiving. Yet at the same time Baba makes it clear that Maya is not to be taken as a mere illusion like the effects it produces. It is not a mere hallucination, or a result of Maya. It is real in the sense that it is an active spiritual principle at work upon the mind. It is not unlike gravity in this sense, that its effect is real (more real actually) yet it has no fabric of its own to be pulled upon. Maya is God's ability to deceive Himself - out of which deception, in stages of imagination, the Universe is formed (via sanskaras) and seen to be real (via Maya). And this deceptiveness permeates in all individual minds as well. In the third set of points given by Baba for the book "The Nothing And The Everything" by Bhau Kalchuri, Maya is clearly defined as "the falsity of the process of thinking", which convinces the unrealized soul that creation is real, when it is only in imagination. Consciousness is born and develops by identifying with shadows in the Nothing. But Maya is not one of these shadows. Out of the Undifferentiated All, Maya is the prime principle which conditions perception, the principle by which perception takes its percept to be the "real thing happening" by ignoring that, in truth, it is perception (seeing) itself that is the only Real thing happening. One's ignorance is not a thing. It is not something external. Nor is it oneself. But it is a fact until it is transcended. Maya is not the devil, or a tempter, or a trickster, or evil, or a demon, a person, or a deva. Nor is Maya a mere abstraction or reductionist philosophical concept. It is the Divine Law that governs the mind in ways that give rise to the kind of ignorance that produces such fantasies. Maya is not bad; for it is through Maya that it is possible to love God or your master, for it is through the veil of Maya that God appears as something apart from your self for you to love. Even the awakening of love is not possible without Maya, nor the rise of consciousness, nor the chance to be good in a world of contrasts. And it is through and in contrast to the illusions produced by Maya that we eventually come to realize our Real Selves. So Maya is not only there to deceive, but to bring about our awakening. 8. Further reading: Discourses by Meher Baba 22 pages on the subject of Maya by Meher Baba Emerson and Sankara The effect of the concept of Maya on the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson by Robert C. Gordon, Ph.D. The favor was later returned when the transcendentalists influenced the thinking of Mahatma Ghandi and the English idealists reinvigorated vedanta in works such as those by Sri Aurobindo. The Nothing and The Everything Extensive treatment of the subject of reality and illusion by Bhau Kalchuri. From points given by Meher Baba. |